- PRODUCTS

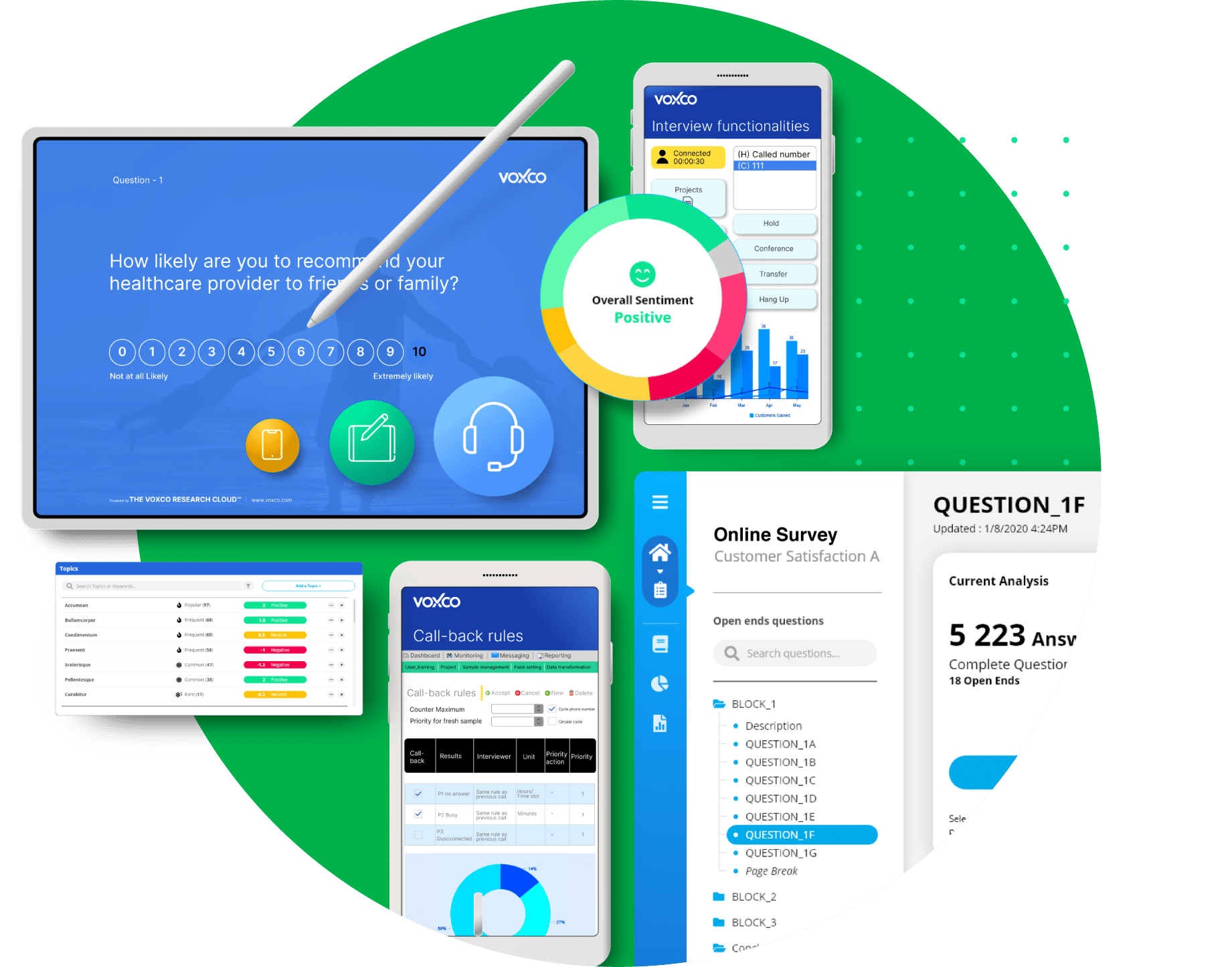

- Voxco Research

- Voxco Intelligence

-

Find the best survey software for you!

(Along with a checklist to compare platforms)

- FEATURES

-

-

-

Take a peek at our powerful survey features to design surveys that scale discoveries.

-

-

- SOLUTIONS

-

-

-

Explore Voxco

Need to map Voxco’s features & offerings? We can help!

-

-

- RESOURCES

-

-

-

Find the best customer experience platform

Uncover customer pain points, analyze feedback and run successful CX programs with the best CX platform for your team.

-

-

- OUR CLIENTS

-

-

-

"

We’ve been avid users of the Voxco platform now for over 20 years. It gives us the flexibility to routinely enhance our survey toolkit and provides our clients with a more robust dataset and story to tell their clients.

Steve Male

VP Innovation & Strategic Partnerships, The Logit Group

-

-

-

-

- COMPANY

- PRICING

- CONTACT US

-

-

-

Explore Regional Offices

-

-

-

-

-

- PRODUCTS

- Voxco Research

- Voxco Intelligence

-

Find the best survey software for you!

(Along with a checklist to compare platforms)

- FEATURES

-

-

Take a peek at our powerful survey features to design surveys that scale discoveries.

-

- SOLUTIONS

-

-

-

Explore Voxco

Need to map Voxco’s features & offerings? We can help!

-

-

- RESOURCES

-

-

-

Find the best customer experience platform

Uncover customer pain points, analyze feedback and run successful CX programs with the best CX platform for your team.

-

-

- OUR CLIENTS

-

-

- "

We’ve been avid users of the Voxco platform now for over 20 years. It gives us the flexibility to routinely enhance our survey toolkit and provides our clients with a more robust dataset and story to tell their clients.

Steve Male

VP Innovation & Strategic Partnerships, The Logit Group

-

-

- COMPANY

- PRICING

- CONTACT US

-

-

Explore Regional Offices

-

-

-

- PRODUCTS

- Voxco Research

- Voxco Intelligence

-

Find the best survey software for you!

(Along with a checklist to compare platforms)

- FEATURES

-

-

-

Take a peek at our powerful survey features to design surveys that scale discoveries.

-

-

- SOLUTIONS

-

-

-

Explore Voxco

Need to map Voxco’s features & offerings? We can help!

-

-

- RESOURCES

-

-

-

Find the best customer experience platform

Uncover customer pain points, analyze feedback and run successful CX programs with the best CX platform for your team.

-

-

- OUR CLIENTS

-

-

-

"

We’ve been avid users of the Voxco platform now for over 20 years. It gives us the flexibility to routinely enhance our survey toolkit and provides our clients with a more robust dataset and story to tell their clients.

Steve Male

VP Innovation & Strategic Partnerships, The Logit Group

-

-

-

-

- COMPANY

- PRICING

- CONTACT US

-

-

-

Explore Regional Offices

-

-

-

-

-

English

English